This was written by Dean Wilson (www.unixdaemon.net).

Implementing configuration management is perfect for green field projects where you can have freedom to choose technical solutions free from most existing technical debt. It's a time where there are no old inconsistencies and you have a window to build, deploy and test all the manifests and recipes without risking user visible outages or interruptions.

Unfortunately, most of us don't have the luxury of starting from scratch in a pristine environment. We have to deal with the oddities, the battle scars, and the need to maintain a good quality of service while evolving and maintaining the platform.

In this article, I'll discuss some of the key points to consider as you begin the journey implementing a configuration management tool in an existing environment. I happen to use puppet and mcollective, but any config management tools will do - find one that works for you.

Discovery

You'll need to start with some discovery (manual, automated, whatever) to learn how your current systems are configured. How many differences are there across the sshd_config files? Where do we use that backup users key? What's the log retention setting of the apache servers? Is it identical between those we upgraded from apache 1 and the fresh apache 2?

When I first started to bring puppet in to my systems, I wrote custom scripts, ssh loops, and inventory-reporting cronjobs to find the information I needed. Now, there is an excellent solution to gather information you need in real time: MCollective.

With the appropriate mcollective agents you can compare, peer, and probe in to nearly every aspect of your infrastructure. The FileMD5er agent, for example, will show you groups of hosts that identical config files. Using this, you can partition the environment and the work, section by section. This will help you find smaller amounts of work to build into puppet.

One of my favourite current tricks is to query config file settings using Augeas in the AugeasQuery agent.

# Does your ssh permit root logins?

$ mco rpc augeasquery query query='/files/etc/ssh/sshd_config/PermitRootLogin' --with-agent augeasquery -v

...

test.example.com : OK

{:matched=>["no"]}

test2.example.com: OK

{:matched=>["yes"]}

No more crazy regexes to find config settings!

You can learn more about how the Blueprint tool can help you with this configuration discovery process in "Reverse-engineer Servers with Blueprint" (SysAdvent 2011, Day 12).

Short Cycles

One of the key factors to consider when starting large scale infrastructure refactoring projects is that you'll need information and you'll need it quickly.

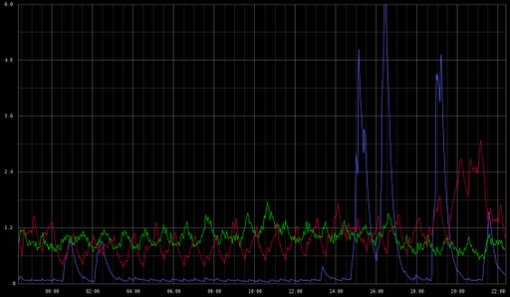

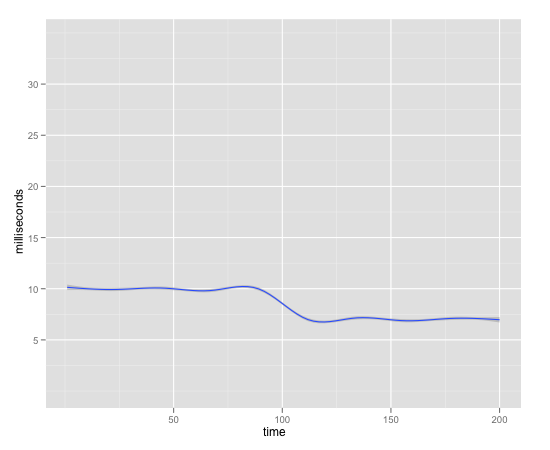

You should always be the first to know about things you've broken. Your monitoring system, centralised logging, trend graphing, and config management systems reporting server (like Puppet Dashboard and Foreman) will become your watchful allies.

The speed at which you can gather information, write the manifest, deploy, and run your tests is more important than you'd think. Keeping this cycle short will encourage you to work in smaller sections, reducing the time between you actually testing your work and keeping the possible problem scope small. Tools like MCollective, mc-nrpe and nrpe runner will enable you to rapidly verify your changes.

Version Control

The short version is: version control everything.

There's no reason, whether you are in a team or working alone (especially when working alone!), to not keep your work in a version control system (such as subversion or git). "That change didn't work, so I've rolled it back". Really? By hand? Are you sure you didn't forget to remove one of the additions? Why would you shoulder the mental burden of knowing all the things you changed recently when there are so many excellent tools that will do it for you and allow easier, auditable rollbacks to old revisions?

Beyond the benefits of providing an ever-present safety net, using a VCS provides a nice way to tie your exact change into incident, audit, or change control systems - a perfect place to do smaller code reviews and a basic, but permanent, collection of institutional knowledge. Being able to search through the puppet logs / reports when debugging an issue to find exactly which resources changed and when, pull up the related changeset and the actual reason for it (and who you should ask for help) changes your process and reports from best guesses based on peoples memories to quick fixes backed by supporting evidence.

On a positive note, it's amazing how much you can learn from reading through commits from things like DBAs doing performance tuning. Seeing which settings were changed and why can save you and your team from forgetting something or making the same mistake or redoing parts of the work again in the future.

Use Packages

Many older environments have fallen in to the habit of pushing tarred applications around (and sometimes compiling software on the hosts as needed). This isn't the best way to deploy in general, and it will make your manifests ugly, complicated, sprawling messes. In most cases, it's not that hard to produce native packages, and tools like fpm make the process even easier.

By actually packaging software and running local repositories you can use native tools, such as yum and apt, in a more powerful way. Processes become shorter and have simpler moving parts, more meta information becomes available, and it's possible to trace the origin of files. You can then use other tools, such as puppet and MCollective to ease upgrades, additions, and reporting.

You can learn more about the world of software packages from "A Guide to Package Systems" (SysAdvent 2011, Day 4).

As an aside, there are differing opinions on whether packages should handle related tasks, such as deploying users. However, once you've reached the point where you can have this argument, you've surpassed most of your peers and will have an environment that gives you the freedom to do whichever you choose.

You can learn more about overlaps in functionality of packaging and config management systems in "Packaging vs Config Management" (SysAdvent 2010, Day 23).

Baked-in Goodness

As you bring more of your system under puppet control, you'll begin to experience the continuously improving system baseline. Every improvement you make is felt throughout the infrastructure, and regressions become infrequent, easy to spot, and quick to remedy. For example, you should never wonder if you've deployed nginx checks to a new server, it should be impossible to have a mysql server without your graphing applied, and every wiki you deploy should be added to the backup system without you intervening.

By having infrastructure manifests such as a monitoring module and writing some generic "add monitoring check" definitions, you can sprinkle reuse throughout other, more functionality-focused modules. In my test manifests, for example, nearly every class has nagios checks associated with it, and every service declares the ports it listens to. This might not sound like much, but it's impossible for me to deploy a server without monitoring, every time I add a new nagios check, all the hosts with that role receive it. Further, generating security policies, firewall rule sets, and audit documents is done automatically for me and requires no manual data gathering. Being able to supply people with links to live documentation is a wonderful way to remove awkward manual steps from reports, audits and inventories.

Involve Everyone

You don't have to agree with the DevOps movement and ideas to use configuration management, but some of its principles (such as communication, openness, shared ownership and responsibility) are worthwhile and have a low overhead once you start to config manage everything. Look for simple requests for information from other teams. Do they want to know which cronjobs run and when? What modules the apache servers have configured? Which rubygems you've deployed on the database servers? (from packages!)

By sharing configuration modules, you help others develop a balanced understanding of the platform. You enable them to regain time wasted raising support tickets through sharing commit logs, audit and error reports, etc, without feeling like your coworkers or customers are wrestling your time away.

At $WORK, a large percentage of our developers are comfortable reading puppet manifests, running MCollective commands, and using custom Foreman pages and cgi-scripts to investigate issues answering their own queries without the sysadmins being involved. This has dropped our workload, given them quicker answers and allowed them to ask targeted questions after doing their own research.

Such things increase efficiency, communication, and happiness.

It's not all about developers either. With a custom puppet define and a little reporting wrapper, we can expose the list of ports required by every machine to our network teams and auditors along with accurate timestamps showing when information was gathered. Using MCollective and custom database facts, our DBAs have dashboards showing deployed packages and services, current running configuration, and the ability to gather ad-hoc real time information from any of our systems: production, development or QA and even compare the differences between them.

Pick your fights

While you're growing accustomed and skilled with your new tools, you need to be aware of the strengths. As the person pushing this change, you have to prove your way is at least as good as (and hopefully better than) the current practise. Because of this, some tasks are bad places to prove your point and you need to be weary of them. Try to find some low hanging fruit

Large monolithic deployments or complex configuration scripts can be handled if you break them down to manageable components. Unfortunately, tight coupling and intertwined code makes these situations bad places to start. It's never a good opening move to start explaining that it took three hours to pick apart a shell script that seems to work fine. Vaguely-defined processes are the other common tar pit. Bringing attention to processes that people seem to do slightly differently is another great way to unite people against what you are trying to accomplish.

You want to avoid resistance caused by confusion. Find and tackle tasks that make sense to put into configuration management, first.

User accounts, for example, are a complex area to automate. While it starts with a simple "deploy the admin accounts, add them to wheel, and push the SSH keys," it can easily become a sprawl of teams needing different sets of access on a semi-rotating basis.

It's worth noting that your config management efforts will often be considered slower, especially when starting out. Writing a ten line throwaway shell script or hand-hacking something will be quicker in the short term than writing clean manifests that include monitoring, meta data and tests but the comparison is unfair. Remember, you're building flexible, reproducible, systems that support future change - not focusing on a single server that just needs to work now and only now.

Roles, not hosts - No more snowflakes

As you build your collection of configuration management techniques, you'll find special snowflake hosts: Machines performing several small but important tasks; ones hand-constructed under time constraints (and needing that one extra special config option) - boxes you'll "only ever have one of," right? Don't fall in the trap of assuming any machine is special or that you'll only ever have one of them. Building a second machine for disaster recovery, a staging version, or even an instance for upgrade tests means there will be times when you'll want more than one of them. If you find yourself adding special cases to your config management "If the hostname is 'foo.example.com'" then it's time to stop, take a step back, and consider alternatives. Any list, especially of resource names, that you hand maintain is a burden and will eventually be wrong.

A sign that things are starting to click is when you stop thinking in terms of hosts and start thinking in roles. Once you begin assigning roles to hosts you will find the natural level of granularity you should be writing your modules at. It's common to revisit previously written modules and extract aspects of them as you discover more potential reuse points.

You can learn more about configuration in terms of roles instead of machines in "Host vs Service" (SysAdvent 2008, Day 7).

Conclusion

With a little care and consideration it's possible to integrate configuration management and even the largest legacy infrastructures while enjoying the same benefits as the newer, less encumbered projects.

Take small steps, master your tools and good luck.

Further Reading