This article written by Stephen Nelson-Smith

Unless you've been living in a remote cave for the last year, you've

probably noticed that the world is changing. With the maturing of automation

technologies like Puppet, the popular uptake of Cloud Computing, and the rise

of Software as a Service, the walls between developers and sysadmins are

beginning to be broken down. Increasingly we're beginning to hear phrases like

'Infrastructure is code', and terms like 'Devops'. This is all exciting. It

also has an interesting knock-on effect. Most development environments these

days are at least strongly influenced by, if not run entirely according to

'Agile' principles. Scrum in particular has experienced tremendous success,

and adoption by non-development teams has been seen in many cases. On the

whole the headline objectives of the Agile movement are to be embraced, but the

thorny question of how to apply them to operations work has yet to be answered

satisfactorily.

I've been managing systems teams in an Agile environment for a number of

years, and after thought and experimentation, I can recommend using an approach

borrowed from Lean systems management, called Kanban.

Operations teams need to deliver business value

As a technical manager, my top priority is to ensure that my teams deliver

business value. This is especially important for Web 2.0 companies - the

infrastructure is the platform -- is the product -- is the revenue. Especially

in tough economic times it's vital to make sure that as sysadmins we are adding

value to the business.

In practice, this means improving throughput - we need to be fixing problems

more quickly, delivering improvements in security, performance and reliability,

and removing obstacles to enable us to ship product more quickly. It also

means building trust with the business - improving the predictability and

reliability of delivery times. And, of course, it means improving quality -

the quality of the service we provide, the quality of the staff we train, and

the quality of life that we all enjoy - remember - happy people make money.

The development side of the business has understood this for a long time.

Aided by Agile principles (and implemented using such approaches as Extreme

Programming or Scrum) developers organise their work into iterations, at the

end of which they will deliver a minimum marketable feature, which will add

value to the business.

The approach may be summarised as moving from the historic model of software

development as a large team taking a long time to build a large system, towards

small teams, spending a small amount of time, building the smallest thing that

will add value to the business, but integrating frequently to see the big

picture.

Systems teams starting to work alongside such development teams are often

tempted to try the same approach.

The trouble is, for a systems team, committing to a two week plan, and

setting aside time for planning and retrospective meetings, prioritisation and

estimation sessions just doesn't fit. Sysadmin work is frequently

interrupt-driven, demands on time are uneven, frequently specialised and

require concentrated focus. Radical shifts in prioritisation are normal. It's

not even possible to commit to much shorter sprints of a day, as sysadmin work

also includes project and investigation activities that couldn't be delivered

in such a short space of time.

Dan Ackerson recently carried out a survey in which he asked sysadmins their

opinions and experience of using agile approaches in systems

work. The general feeling was that it helped encourage organisation,

focus and coordination, but that it didn't seem to handle the reactive nature

of systems work, and the prescription of regular meetings interrupted the flow

of work. My own experience of sysadmins trying to work in iterations is that

they frequently fail their iterations, because the world changed (sometimes

several times) and the iteration no longer captured the most important things.

A strict, iteration-based approach just doesn't work well for operations -

we're solving different problems. When we contrast a highly interdependent

systems team with a development team who work together for a focussed time,

answering to themselves, it's clear that the same tools won't necessarily be

appropriate.

What is Kanban, and how might it help?

Let's keep this really really simple. You might read other explanations

making it much more complicated than necessary. A Kanban system is simply a

system with two specific characteristics. Firstly, it is a pull-based system.

Work is only ever pulled into the system, on the basis of some kind of signal.

It is never pushed; it is accepted, when the time is right, and when there is

capacity to do the work. Secondly, work in progress (WIP) is limited. At any

given time there is a limit to the amount of work flowing through the system -

once that limit is reached, no more work is pulled into the system. Once some

of that work is complete, space becomes available and more work is pulled into

the system.

Kanban as a system is all about managing flow - getting a constant and

predictable stream of work through, whilst improving efficiency and quality.

This maps perfectly onto systems work - rather than viewing our work as a

series of projects, with annoying interruptions, we view our work as a constant

stream of work of varying kinds.

As sysadmins we are not generally delivering product, in the sense that a

development team are. We're supporting those who do, addressing technical debt

in the systems, and looking for opportunities to improve resilience,

reliability and performance.

Supporting tools

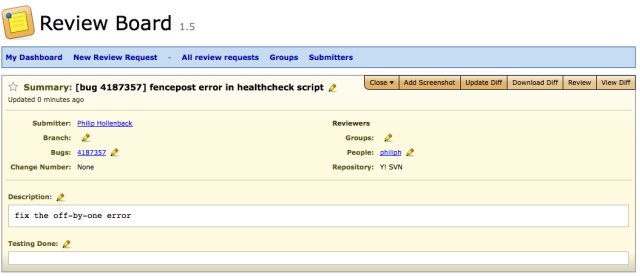

Kanban is usually associated with some tools to make it easy to implement

the basic philosophy. Again, keeping it simple, all we need is a stack of

index cards and a board.

Stephen's (the author) Kanban board.

The word Kanban itself means 'Signal Card' - and is a token which represents

a piece of work which needs to be done. This maps conveniently onto the agile

'story card'. The board is a planning tool, and and an information radiator.

Typically it is organised into the various stages on the journey that a piece

of work goes through. This could be as simple as to-do, in-progress, and done,

or could feature more intermediate steps.

The WIP limit controls the amount of work (or cards) that can be on any

particular part of the board. The board makes visible exactly who is working

on what, and how much capacity the team has. It provides information to the

team, and to managers and other people about the progress and priorities of the

team..

Kanban teams abandon the concept of iterations altogether. As Andrew

Shafer once said to me: "We will just work on the highest priority 'stuff',

and kick-ass!"

How does Kanban help?

Kanban brings value to the business in three ways - it improves trust, it

improves quality and it improves efficiency.

Trust is improved because very rapidly the team starts being able to deliver

quickly on the highest priority work. There's no iteration overhead, it is

absolutely transparent what the team is working on, and, because the

responsibility for prioritising the work to be done lies outside the technical

team, the business soon begins to feel that the team really is working for

them.

Quality is improved because the WIP limit makes problems visible very

quickly. Let's consider two examples - suppose we have a team of four

sysadmins:

The team decides to set a WIP limit on work in progress of one. This means

that the team as a whole will only ever work on one piece of work at a time.

While that work is being done, everything else has to wait. The effects of

this will be that all four sysadmins will need to work on the same issue

simultaneously. This will result in very high quality work, and the tasks

themselves should get done fairly quickly, but it will also be wasteful. Work

will start queueing up ahead of the 'in progress' section of the board, and the

flow of work will be too slow. Also it won't always be possible for all four

people to work on the same thing, so for some of the time the other sysadmins

will be doing nothing. This will be very obvious to anyone looking at the

board. Fairly soon it will become apparent that the WIP limit of one is too

low.

Suppose we now decide to increase the WIP limit to ten. The syadmins go

their own ways, each starting work on one card each. The progress on each card

will be slower, because there's only one person working on it, and the quality

may not be as good, as individuals are more likely to make mistakes than pairs.

The individual sysadmins also don't concentrate as well on their own, but work

is still flowing through the system. However fairly soon, something will come

up which makes progress difficult. At this stage a sysadmin will pick another

card and work on that. Eventually two or three cards will be 'stuck' on the

board, with no progress, while work flows around them owing to the large WIP

limit. Eventually we might hit a big problem, system wide, that halts progress

on all work, and perhaps even impacts other teams. It turns out that this

problem was the reason why work stopped on the tasks earlier on. The problem

gets fixed, but the impact on the team's productivity is significant, and the

business has been impacted too. Has the WIP limit been lower, the team would

have been forced to react sooner.

The board also makes it very clear to the team, and to anyone following the

team, what kind of work patterns are building up. As an example, if the team's

working cadence seems to be characterised by a large number of interrupts,

especially for repeatable work, or to put out fires, that's a sign that the

team is paying interest on technical debt. The team can then make a strong

case for tackling that debt, and the WIP limit protects the team as they do so.

Efficiency is improved simply because this method of working has been shown

to be the best way to get a lot of work through a system. Kanban has its

origins in Toyota's lean processes, and has been explored and used in dozens of

different kinds of work environment. Again, the effects of the WIP limit, and

the visibility of their impact on the board makes it very easy to optimise the

system, to reduce the cycle time - that is to reduce the time it takes to

complete a piece of work once it enters the system.

Another benefit of Kanban boards is that it encourages self-management. At

any time any team member can look at the board and see at once what is being

worked on, what should be worked on next and, with a little experience, can see

where the problems are. If there's one thing sysadmins hate, it's being

micro-managed. As long as there is commitment to respect the board, a sysops

team will self-organise very well around it. Happy teams produce better

quality work, at a faster pace.

How do I get started?

If you think this sounds interesting, here are some suggestions for getting

started.

Have a chat to the business - your manager and any internal stakeholders. Explain to them that you want to introduce some work practices that will improve quality and efficiency, but which will mean that you will be limiting the amount of work you do - i.e. you will have to start saying no. Try the puppy dog close: "Let's try this for a month - if you don't feel it's working out, we'll go back to the way we work now".

Get the team together, buy them pizza and beer, and try playing some Kanban games. There are a number of ways of doing this, but basically you need to come up with a scenario in which the team has to produce things, but the work is going to be limited and only accepted when there is capacity. Speak to me if you want some more detailed ideas - there are a few decent resources out there.

Get the team together for a white-board session. Try to get a sense of the kinds of phases your work goes through. How much emergency support work is there? How much general user support? How much project work? Draw up a first cut of a Kanban board, and imagine some scenarios. The key thing is to be creative. You can make work flow left to right, or top to bottom. You can use coloured cards or plain cards - it doesn't matter. The point of the board is to show what work is being done, by whom, and to make explicit what the WIP limits are.

Set up your Kanban board somewhere highly visible and easy to get to. You could use a whiteboard and magnets, a cork board and pins, or just stick cards to a wall with blue tack. You can draw lines with a ruler, or you can use insulating tape to give bold, straight dividers between sections. Make it big, and clear.

Agree your WIP limit amongst yourselves - it doesn't matter what it is - just pick a sensible number, and be prepared to tweak it based on experience.

Gather your current work backlog together and put each piece of work on a card. If you can, sit with the various stakeholders for whom the work is being done, so you can get a good idea of what the acceptance criteria are, and their relative importance. You'll end up with a huge stack of cards - I keep them in a card box, next to the board.

Get your manager, and any stakeholders together, and have a prioritisation session. Explain that there's a work in progress limit, but that work will get done quickly. Your team will work on whatever is agreed is the highest priority. Then stick the highest priority cards to the left of (or above) the board. I like to have a 'Next Please' section on the board, with a WIP limit. Cards can be added or removed by anyone from this board, and the team will pull from this section when capacity becomes available.

Write up a team charter - decide on the rules. You might agree not to work on other people's cards without asking first. You might agree times of the day you'll work. I suggest two very important rules - once a card goes onto the in progress section of the board, it never comes off again, until it's done. And nobody works on anything that isn't on the board. Write the charter up, and get the team to sign it.

Have a daily standup meeting at the start of the day. At this meeting, unlike a traditional scrum or XP standup, we don't need to ask who is working on what, or what they're going to work on next - that's already on the board. Instead, talk about how much more is needed to complete the work, and discuss any problems or impediments that have come up. This is a good time for the team to write up cards for work they feel needs to be done to make their systems more reliable, or to make their lives easier. I recommend trying to get agreement from the business to always ensure one such card is in the 'Next Please' section.

Set up a ticketing system. I've used RT and Eventum. The idea is to reduce the amount of interrupts, and to make it easy to track whatever work is being carried out. We have a rule of thumb that everything needs a ticket. Work that can be carried out within about ten minutes can just be done, at the discretion of the sysadmin. Anything that's going to be longer needs to go on the board. We have a dedicated 'Support' section on our board, with a WIP limit. If there are more support requests than slots on the board, it's up to the requestors to agree amongst themselves which has the greatest business value (or cost).

Have a regular retrospective. I find fortnightly is enough. Set aside an hour or so, buy the team lunch, and talk about how the previous fortnight has been. Try to identify areas for improvement. I recommend using 'SWOT' (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) as a template for discussion. Also try to get into the habit of asking 'Five Whys' - keep asking why until you really get to the root cause. Also try to ensure you fix things 'Three ways'. These habits are part of a practice called 'Kaizen' - continuous improvement. They feed into your Kanban process, and make everyone's life easier, and improve the quality of the systems you're supporting.

The use of Kanban in development and operations teams is an exciting new

development, but one which people are finding fits very well with a devops kind

of approach to systems and development work. If you want to find out more, I

recommend the following resources:

- the home of Kanban for software development; A central place where ideas, resources and experiences are shared.

- mailing list for people deploying Kanban in a software environment - full of very bright and experienced people

- the nascent devops movement

- agile web operations - excellent blog covering all aspects of agile operations from a devops perspective

- agile sysadmin - This author's own blog - focussed around the practical application of technology and agile processes to deliver business value