By: Alejandro Brito Monedero (@ae_bm)

Edited By: J. Paul Reed (@jpaulreed)

We are living interesting times in the tech world, full of trendy technologies, like cloud computing, containers, schedulers, and serverless.

They’re all rainbows and unicorns when they work. But we can start to forget about the systems that support our abstractions until they break, and we have to give our best to fix them.

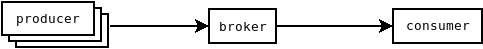

Some time ago in one of our multiple pub-sub systems, there were some processes publishing messages to a message broker. Those messages are consumed by a process running in a container. So far this isn’t too exotic; it’s easy to diagram out:

For the most part, this system worked as expected. However, at one point, we received some alerts from the monitoring system. Those alerts reported that the broker had a lot of queued messages and no consumers connected. Our first reaction was to restart the consumer container and call it a day. But the error kept happening, always at the worst possible time.

While taking a closer look at the problem, we confirmed that the broker has no consumers to deliver the messages. The surprise came when we inspect the consumer container. It was still running and seemingly all was well, except we did notice it was blocked on the socket used to communicate with the broker. When we inspect the socket statistics inside the container’s network namespace, it showed a connection to the broker:

# ss -tpno

ESTAB 0 0 <container ip>:<some port> <broker ip>:<broker port>Upon seeing this, our reaction could pretty much be summed up as:

The problem seemed to be that the connection state between the broker and consumer was not synchronized. In the host network namespace (where the broker is running), the status showed there weren’t any TCP connection from the container. Instead in the container network namespace there is an established connection to the broker. Our dear RFC 793 mentions this situation Half-Open Connections and Other Anomalies (emphases mine):

An established connection is said to be “half-open” if one of the TCPs has closed or aborted the connection at its end without the knowledge of the other, or if the two ends of the connection have become desynchronized owing to a crash that resulted in loss of memory. Such connections will automatically become reset if an attempt is made to send data in either direction. However, half-open connections are expected to be unusual, and the recovery procedure is mildly involved.

If at site A the connection no longer exists, then an attempt by the user at site B to send any data on it will result in the site B TCP receiving a reset control message. Such a message indicates to the site B TCP that something is wrong, and it is expected to abort the connection.

After that nice enlightenment, we started to think of possible causes for that “desynchronization.” Options that came to mind included:

- the broker restarting or crashing

- man-in-the-middle attack (MITM)

- A grumpy kernel (iptables, ebtables, bridges, etc)

- A grumpy container engine

- Some Lovecraftian horror show

To determine which it was, we first checked if the broker has crashed or has been restarted. Upon inspection, we found it’d been running for a long time and other systems using it were working normally. So it wasn’t a problem with the broker.

The kernel iptables and bridge didn’t show anything weird. A MITM attack seemed a bit exotic. The other options were hard to prove, and we thought it wouldn’t be very professional of us to blame the container system without any evidence. ;-)

While trying to think of other causes it could be, we kept tcpdump running on one of consumer containers. tcpdump captured an RST message sent from the container IP to the broker in response to the broker sending a data message to the consumer container after a long period of inactivity. The weird thing is that network traffic never reached the container, neither the RST originated from the container. Maybe the MITM attack wasn’t such an exotic possibility after all?!

Meanwhile, while trying to re-create the problem end state and work toward making our our systems resilient to this situation: we used iptables to drop or reset traffic from the broker to the container after the container connected to the broker. Both methods allowed us to observe the same end-state we were getting in production, confirming the container never learns that the broker connection is lost. Figuring out how to find how to learn that your peer is down even if the TCP connection state is established proved difficult. But after some Internet searching, we found RFC 1122’s section on TCP Keep-Alives (again emphases mine):

Implementors MAY include “keep-alives” in their TCP implementations, although this practice is not universally accepted. If keep-alives are included, the application MUST be able to turn them on or off for each TCP connection, and they MUST default to off.

Keep-alive packets MUST only be sent when no data or acknowledgement packets have been received for the connection within an interval*. This interval MUST be configurable and MUST default to no less than two hours.

…

DISCUSSION:

A “keep-alive” mechanism periodically probes the other end of a connection when the connection is otherwise idle, even when there is no data to be sent. The TCP specification does not include a keep-alive mechanism because it could:

(1) cause perfectly good connections to break during transient Internet failures; (2) consume unnecessary bandwidth (“if no one is using the connection, who cares if it is still good?”); and (3) cost money for an Internet path that charges for packets.…

A TCP keep-alive mechanism should only be invoked in server applications that might otherwise hang indefinitely and consume resources unnecessarily if a client crashes or aborts a connection during a network failure.

Translation: distributed systems are fun… and determining whether a connection is still valid is often the cherry on top.

But before trying to poke at the TCP stack, we kept investigating. We found out that AMQP supports heartbeats, and they are used to check if a connection is still valid. The library we were using had this option disabled by default, which explains why the container was blocked and waiting instead of trying to reconnect to the broker. To make things worse because the container is a consumer, it never sends data to the broker. If the container has sent data using the same socket it could detect on its own whether the connection was still valid.

To fix this, we evaluated two solutions:

- The TCP keep-alive fix was the fastest to implement, but we didn’t like it because it deletgated detection of the broken connection to the kernel TCP implementation. Also we didn’t really want to mess with kernel socket options.

- For an alternative, we ran some tests with other applications and they handled it at the application level (thank you Bandwagon effect). Through this testing, we found we could change the library to activate the AMQP heartbeats. It took more time, but it felt like a better solution to use the mechanisms provided by the AMQP protocol.

But what about the MITM attack we thought we were seeing?

First some context: we run periodic, short-lived helper containers. We have observed with tcpdump that when a container starts, it announces some ICMPv6 memberships. Also by default, the container network namespace is attached to a network bridge. The network bridge uses a cache to associate addresses with its respective port, like a network switch. It populates this table when it sees network traffic; as you might imagine, if there isn’t any traffic for some time, the data in the table becomes stale.

The MITM “attack” happens when in a period without traffic between the broker and the container, the bridge cache is stale and a short live container is launched, there is a chance for it to get the same IP address the consumer container has. This new container changes the bridge cache, then if the broker sends a message to the consumer, the bridge delivers it to the new container, who then answers with a TCP RST because it doesn’t have a TCP connection with the broker. Finally the broker receives the TCP RST and aborts its connection with the consumer. The magic of giving the same IP address to different containers.

A picture is worth a thousand words.

Without the MITM

With the MITM

Ultimately, the problem turned out to be one of the most exotic possibilities we had come up with, making us feel pretty:

Conclusion

Our programs must be prepared to handle network disruptions even when the network traffic doesn’t leave a single host and you are using containers. Remember: the network is not reliable! If we forget this, we will have a lot of “fun” with distributed systems bugs.

Perhaps more importantly: always remember that if your program never sends traffic on its TCP socket, you can’t be sure whether the connection is valid or if you will end up waiting for a message that will never arrive.

There are two solutions to avoid this situation: the first is to use TCP keepalives and delegate detection of stale connections to the OS; The other is to implement or use a heartbeat mechanism at a higher layer in the protocol.

Both alternatives have their pros and cons, so you’ll need to find which one is best for your team and hte distributed system you run. But now that you’ve seen a story where TCP half-open connections, “anomelies,” and keep-alives all worked together, you’ll know that MITM “attack” might not be such an exotic cause of the problem, even if it’s not an attacker trying to get in, but rather your own the kernel.

Extras

While preparing this post, I found this article, which discusses half open connections; it would have been handy when explaining this problem to my coworkers.

No comments :

Post a Comment